The play of light in the atmosphere is an endless source of fascination for me. The blue of the sky and the colours of the sunset are just the beginning of a cornucopia of optical phenomena. This morning’s walk along the lakeshore revealed three others.

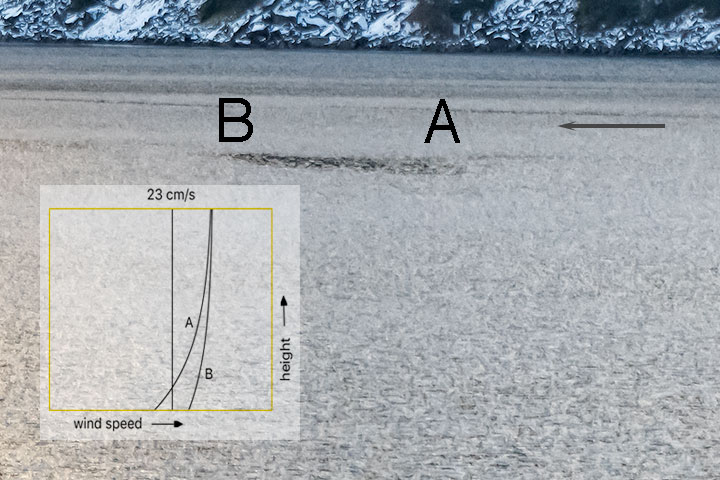

The Harrop ferry appears as a two-image inferior mirage. It results from the refractive bending of light by the strong temperature gradient that accompanies cold air over warmer water. The term, inferior, is not an editorial comment, but a statement that the position of the image (what is seen) is lower than that of the object (what would be seen in the absence of refraction). Both the erect and inverted images have been displaced downwards, and parts of each have vanished, as has the lake surface in the distance. Incidentally, a mirage is not an optical illusion any more than is, say, an image in a mirror or binoculars. It is merely an image formed when the atmosphere acts as a lens — although a mirage’s appearance is more akin to those of a carnival house of mirrors.

A sundog (or parhelion) was seen about 22° to the left of the sun. This is an image of the sun that has been displaced and dispersed (colours separated) by hexagonal ice crystals, each of which was acting as a prism. That the sundog appears to the left or right of the sun, but not elsewhere is a result of these crystals being large enough to become aerodynamically oriented so they fall rather like dinner plates on a table. Incidentally, the name sundog was gained because this phenomenon follows the sun around the sky, rather like a dog following its master. The formal term, parhelion, just means beside the sun.

Iridescence. Appearing much closer to the sun than a sundog and caused by water drops rather than ice crystals is iridescence. And unlike a sundog, the light does not pass through the drops, but is merely deviated as it flows around them as obstacles. However, the amount of deviation is dependent upon the wavelength of the light, so colours are separated in the cloud.