Local wildfire smoke from this grim season had all but vanished when more flowed in from the south. As uncomfortable as it is, the smoke provides the hazy air that easily enables the identification of Mach bands.

Mach bands are not a feature of the external natural world. Rather, they arise in the eye and are an optical illusion first explained by Ernst Mach (1838–1916). The bands result from a process in our retinas that enhances contrast. Consequently, they appear subtly in everything we see, whether it is a view of the external world or just a picture of that view. However, the bands are never so apparent as when looking at step-like transitions in brightness. A succession of distant ridges seen through a smoky haze provides an ideal place to examine them.

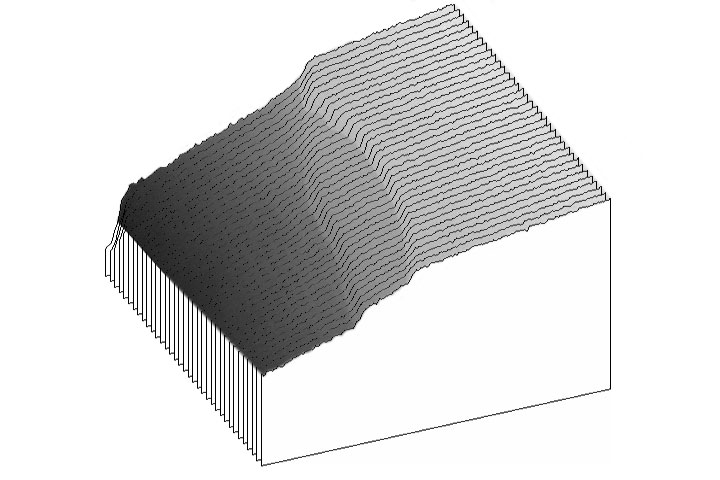

Consider the receding ridges in the centre of this scene looking across the Lake. Each ridge seems to be edged with a thin diffuse dark band which contrasts with an adjacent brighter band on the ridge beyond it. Neither band is present in the external world; they are creations of our eyes.

Here is a detail from the centre left of the picture where one ridge passes behind another. The picture has been rendered in black and white, but the thin Mach bands are readily apparent.

When the brightness is plotted for the picture detail, the two cliffs marking the shift from one ridge to the next are apparent. Yet this quantitative analysis does not show the bands that the eye perceives: there is no small trench on the dark side of the cliff or small ridge on the bright side. Mach bands are an illusion created by one’s own image processing. Our subjective view differs from the objective scene.

So, whether we are viewing the external natural scene or your photographic (digital) images of that scene, the Mach band are only perceived through our retinas? Another amazing attribute of the biological human machine.

Tom, yes. Whatever your eyes see is processed in a way that the contrast of edges is enhanced. It is usually only in scenes, such as I presented, that both logic and measurement show that the feature is in the eyes rather than in the scene, itself. Incidentally, our retina is not alone in processing a scene in this way, a Xerox machine does likewise, as do most computer algorithms that perform image sharpening.

This in incredibly fascinating, Alistair. I can’t wait to share this information with others – truly amazing, and something I would not have learned if not for your knowledge and your love of sharing natural phenomena with the rest of us.

Thank you.