A pair of Hooded Mergansers on the Lake this morning unexpectedly raised their crests. It seems a few months too early for such courting behaviour.

Are Hooded Mergansers courting in December?

A pair of Hooded Mergansers on the Lake this morning unexpectedly raised their crests. It seems a few months too early for such courting behaviour.

Are Hooded Mergansers courting in December?

And now there came both mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold:

And ice, mast-high, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1798)

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Green ice holds an almost mystical status among aficionados of cold. Coleridge mentions green icebergs in 1798, and there have been a handful of similar observations through subsequent centuries.

Although green ice is uncommon, it can be seen locally, not in icebergs, but in anchor ice.

The recent cold snap brought anchor ice to local creeks. I offered an explanation of how ice forms on the creek bed three years ago, so that need not be repeated here. However, an explanation seems in order for the fact that on both occasions the ice on the stream bed appeared jade.

How can ice be green? The explanation offered below involves two processes: one that primarily absorbs light at the reddish end of the visible spectrum; the other that primarily absorbs light at the blueish end. What remains is light from near the spectral middle: green.

Specious guesswork

It is worth dismissing the standard glib suggestion that such an unusual colour arises from embedded impurities. All the water from which this ice formed is remarkably clean and free of sediments and biota (it is winter). The colour seen is a characteristic of the ice and lighting, not suspended dirt.

Facts

Begin with what is known: both water and ice are intrinsically blue. This might seem at variance with common experiences of seeing a glass of water or an ice cube, but each has a rather small volume. To see the blue, a light absorption path of metres (not centimetres) is needed. Look down a deep hole punched in snow. It is blue, as is the light in an ice cave or that which reaches the bottom of a lake. (Of course, the light seen when looking down on top of a lake or glacier is complicated by surface reflections.) When visible light passes through water or ice the greatest absorption is at the red end of the spectrum. There is a progressive decline in absorption through the orange, yellow and green with the least absorption being at the blue end. Energy remains throughout the spectrum, but the eye perceives the composite as blue.

Anchor ice is resting on an ochre stream bed (2013).

Path-length problem

Leaving aside that the aim is to explain green, not blue, it would seem that the anchor ice in the picture below is too thin to give the long absorption path needed for seeing colour. However, anchor ice is rather porous (see previous explanation), having many internal surfaces between ice and water that scatter the light to and fro as if in a pinball machine. So, light travels a tortuous path that is vastly greater than the ice thickness and certainly sufficient to give the transmitted light a bluish cast.

Ochre stream bed

The bluish light that passes through the anchor ice reaches a characteristically earthy coloured stream bed. While absorption in the ice largely removed the reddish end of the spectrum, absorption by the stream bed now largely removes the bluish end of the spectrum. The dominant light that re-emerges from the ice is in the relatively undiminished middle of the spectrum: green.

Last Saturday at the height of the cold snap, anchor ice offered the best local example of green ice.

Green icebergs

Offered was a plausible explanation of the green of anchor ice. However, is it in any way applicable to the icebergs described by Coleridge and others? Yes, somewhat. What was apparent with the anchor ice was that it involved two counteracting processes: ice that absorbed the reddish end of the spectrum and something else that depleted the bluish end. With anchor ice, that something else was absorption by the ochre stream bed. For green icebergs, this is replaced by atmospheric scattering that reddens the illumination from the low polar Sun. The result is much the same: green ice.

It wasn’t the best I had seen, but this display of haloes in the direction of Nelson was better than any I had seen for a few years. I was alerted to it by the sight of a circumzenithal arc high over a rooftop, but then grabbed my camera and found a better view of the western sky.

The circumzenithal arc appears high in the sky when the Sun is low. It is concave up as befits its name: it being a (portion of a) circle centred on the zenith. Below the circumzenithal is the supralateral tangential arc to the 46° halo. It is fainter and is concave down. When the Sun is about 23° above the horizon, the two arcs touch, at which time the colours of the circumzenithal are superb (better than those of a rainbow). When this picture was taken, the Sun was only about 14° above the horizon, the arcs have moved apart and the colours lack the earlier purity.

With a better view, more details emerged. In addition to the mentioned arcs there are other faint features: a 22° halo, a sun pillar, a Lowitz arc and crepuscular rays. Not all that shabby.

As dippers worked a creek, it seemed as if they were pearl divers searching for rare golden orbs.

If judged solely by appearance, the dipper is a nondescript little bird. That assessment changes when one watches the bird’s antics: It is a songbird that flies underwater to collect comestibles in swift mountain streams. Its palate appreciates items from aquatic arthropods to fry, but particularly prized seem to be the fertilized golden eggs of the Kokanee salmon. True, the bird will also accept the unfertilized pearly-white eggs, but it seems to favour golden orbs.

A dipper retrieved three golden pearls and placed two on an ice shelf to be downed one at a time.

Ducks seen along the lakeshore over the last few days ranged in weight from about 370 to 5000 g.

A duck of our winter waterways the Bufflehead Duck, at about 370 g, is second in tininess to the slightly smaller Green-winged Teal. This bufflehead is a male.

Still a fairly small duck, but at about 600 g, the Wood Duck is 60% heavier than the bufflehead. The female is on the left and the male is on the right.

At about 1100 g, the Mallard is about 80% heavier than the Wood Duck. There are a number of male and female mallards in this picture, but the giant in the centre is a Rouen Duck. At about 5000 g, it weighs over four times that of the mallard, but is a domestic breed of its smaller cousin. This escapee was also seen hanging out with mallards about two years ago (Rouen Duck).

In … Mount Revelstoke Park, mortality of siskins and other winter finches … has been seen frequently enough over the last 25 years that they are called “grill birds” by the local inhabitants, in reference to their propensity to be collected by the front end of moving vehicles. http://iceandsnowtechnologies.com/articles/WildlifeSD.pdf

When I saw hundreds of Pine Siskins feeding on highway salt, I knew some would become grill birds.

As a vehicle approached, the siskins would take to the air.

But, depending upon the speed and size of the vehicle (which never slowed) the grill collected some.

No problem, the rest alighted again, sometimes continuing to feed amongst their fallen colleagues.

“In exchange for road salt, we happily do the danse macabre.”

A recurring theme of mine over the years has been that of a katabatic wind: the gentle stream of air that flows down a mountainside overnight. Indeed, I wrote about it fifty years ago, again this year with 23 cm/s, and with many postings in between.

Barney Gilmore, who has a grand view across the North Arm of the Lake, today sent me a wonderful picture illustrating a katabatic wind. It was taken in the light of dawn and shows smoke (from slash burning) being transported down the mountain slope and out over the Lake by a katabatic wind.

I am really impressed with such compelling illustrations of a physical process as this.

Barney Gilmore’s picture is used with permission.

The bird sources are consistent: the dipper is a bird of clear mountain streams where it dives and scours creek bottoms for comestibles. Yet, with the approach of winter, this unusual songbird often moves downstream to lower elevations — presumably to avoid freezing creeks. Around here, that means that dippers spread out along the shore of Kootenay Lake each fall. This behaviour seems to have been baked into them: Whether or not the creek freezes, when the weather cools, many start to hunt along the lakeshore.

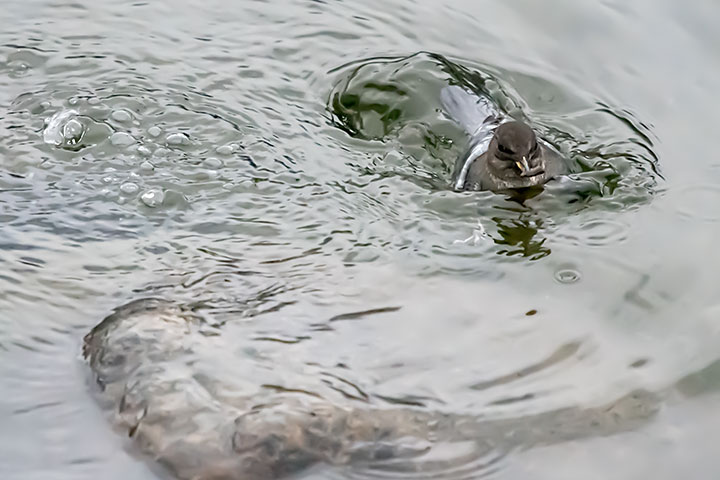

This is one of a number of dippers seen hunting along the lakeshore in recent weeks. It first dived from the rock at the picture bottom. It disturbed the water on the left, and then began to surface, upper right, having captured something in its bill.

Arising out of the depths, it clutches what is probably a caddisfly larva in its bill.

It does not swallow it in the water, but takes it to a rock in the stream.

And there downs its prize.

“Burp.”

The West Arm waterbird count has been conducted since 1974, but I am only a recent participant. Yesterday, most of the interesting birds were seen far out on the Lake and so did not produce good images. However, one land bird did.

A (fist-sized) Pygmy Owl was hunting from a tree branch in Kokanee Creek Park.

Santa Claus

When out on the roof there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.

Just as the poem says, early this Christmas morning I really did hear a clatter on my roof and I sprang from my chair to see what was the matter.

There he was on my chimney, replete with a white-trimmed red cap. I’m not making this up — I took a picture.

The truth is out: Santa Claus is a Pileated Woodpecker.