|

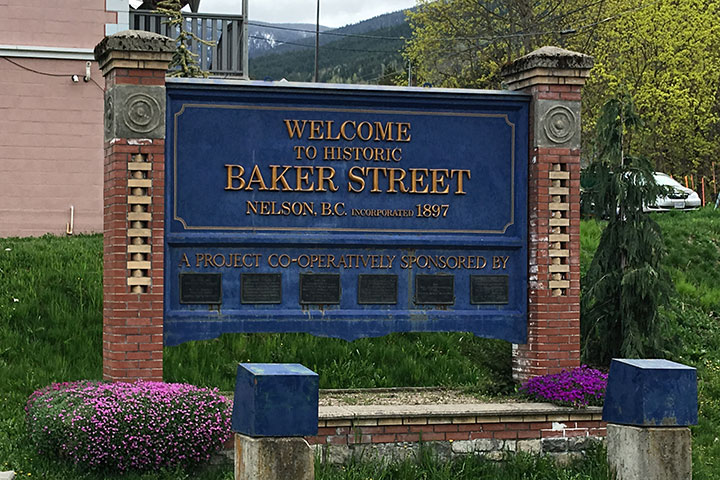

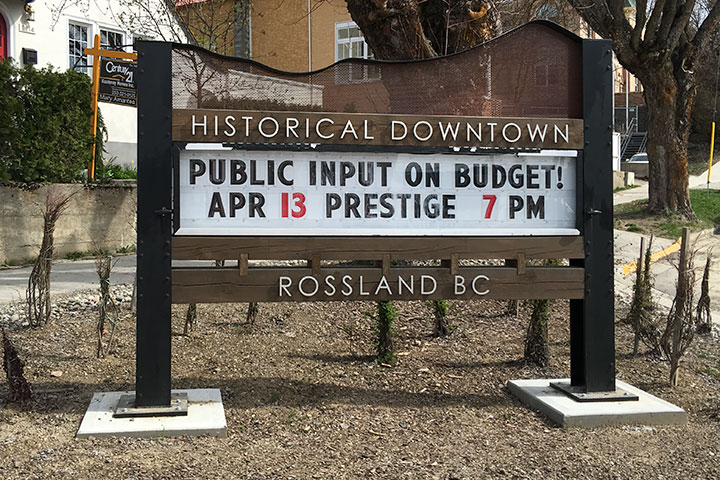

Two days ago, when I posted pictures of two municipal signs, I mentioned a dictionary and so hinted that my concern was linguistic. Many people found the designs of the signs to be the thing of primary interest. My take on the designs is that, in part, they are intended to serve different functions. Rossland’s seems directed at locals as it announces municipal events. Nelson’s sign (top image) seems directed at tourists by lending gravitas to Baker Street. However, I believe that each design rather nicely speaks of its town’s history. Consider Nelson’s. The use of bricks speaks of an early municipal decision to reduce the number of burning buildings by requiring masonry construction. The columns mimic those in the Mara-Barnard Block (second image), built in 1897 (421-31 Baker St.). And the sign’s other decorations reflect early building ornamentation. Thought was put into this. Although Rossland’s sign (third image) is very different, it too speaks of the city’s past: one of wood and iron. My family lived in Rossland from 1896 until 1979. During my childhood, there were still wooden mining buildings on the mountainside, and long railway trestles across ravines. Iron rails, wheels, spikes and equipment were still strewn on the slopes. One rather nice touch on the sign is the use of an iron finial to suggest the city’s iconic mountain skyline. The point of iron and wood is underscored with a picture (fourth image) taken by my grandfather, Oswald Bisson, about the year, 1900. It shows a railway trestle, which looks largely of wood, but then think about the rails, spikes and all those bolts. The trestle was still there when I was a small child and once I scared myself thoroughly by trying to walk across it.

However, the distinction I was trying to make with my previous posting was about the way the two cities chose to speak of history. The word, history, has two adjectival forms: historic and historical. They have different meanings, meanings that have persisted in the language for about 250 years. It is not unusual for a noun to spawn multiple adjectives which emphasize different aspects. Consider child. It spun off childlike (innocence and curiosity) and childish (immature and silly). Or think of simple, which produced simplify (reduced to its essence) and simplistic (stripped of its essence). In like manner, historical and historic have different meanings. Historical means of, or concerned with, history. An old thing, when discussed as such, is historical. By using, historical, Rossland was emphasizing the older aspects of the city as distinct from, say, its concrete sidewalks (they used to be wooden), or its Wi-Fi stations. Historic means famous or renowned in history. Within the Canadian context, the Plains of Abraham (1759) are historic; Mackenzie’s arrival at Bella Coola (1793) is historic; Confederation (1867) is historic; Craigellachie (1885) is historic; Quebec referendums (1980, 1995) are historic; yesterday’s Supreme Court ruling on Métis’ rights is historic (2016). Historic does not mean: we are proud of the job we did in restoring our buildings. One measure of something being historic is how widely it is taught and discussed (paid promoters don’t count in such a tally). Are school children in Ontario taught about the historic significance of Baker Street? Well no, not even Nelson’s children are. Rossland, with historical, got it right; Nelson, with historic, got it wrong. Should anyone care about how we present ourselves? Maybe most do not — but I do. Nelson has so much going for it: a beautiful setting betwixt mountains and lake (fifth image); a vibrant cultural scene (sixth image); abundant nature (seventh image); and interesting historical architecture (last image). Nelson should not feel the need to present itself as something it is not: historic. |

|

-

Recent Posts

- Pygmy Owl

- Pileated male or female

- Spike elk

- Glory & cloudbow

- Trumpeter Swans

- Two uncommon birds

- Gull and fish

- Clark’s Nutcracker

- Blue Jay

- Aurora and life

- Dowitcher redux

- Mountain Chickadee

- Long-billed Dowitcher

- Osprey & fish

- Otters return

- Partial lunar eclipse

- Mountain goats

- Otters return

- Season to change

- Bingo

- August goulash

- Bear ate wasps

- Bear eats Kokanee

- Rough-winged Swallow

- Big juvenile birds

- Hummingbird pee

- Male black-chinned here

- Wildlife mating

- Heron & mallard

- July goulash

- Ibis

- Pulp collection

- Scraggly eagle & ghost

- Snowshoe hare

- Kingbird chicks

- Coming and going

- Horned Grebe

- Sapsuckers nesting

- Headdress

- Crab spider

- Tadpoles

- Tree Swallows mating

- Yellow warbler nest

- Dipper chicks

- Marmot pups

- Osprey mating

- California quail

- May goulash

- Hummingbirds, plus

- Eagle’s lost nest

Archives

Categories

Subscribe/Unsubscribe

You never cease to amaze! And now we will admire you as a lexophile!

Margo, musings communicated through images and words.