The varying patterns that can be seen on our lake are endlessly fascinating. Photographers often seek out particularly beautiful ones, as do I, but I also seek the beauty of its physics.

Pop pattern posting: With over 6500 viewings spread over a decade, the posting about Lake-surface patterns during rain is uncomfortably close to being viral for this unpretentious blog.

On occasion, this blog and website have treated various lake-surface patterns: ripples, gravity waves, wind-driven waves, wakes, beach cusps, convergence, divergence, long-shore drift, and patterns from rain. The latest observation was prompted by thoughts about the patterns produced by katabatic winds.

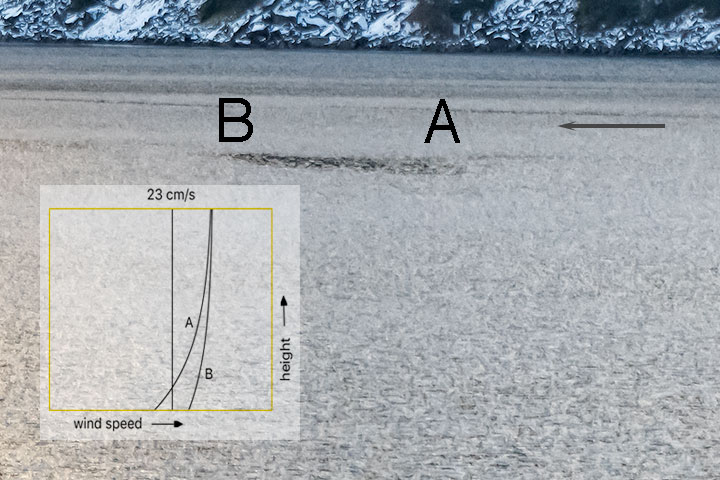

The pattern of interest is this unremarkable-looking patch of calm water amidst a wind ruffled surface. For reference, I note that there is a gentle flow of water from left to right, and a gentle flow of air (wind) from right to left. The calm patch could have resulted from either a locally decreased water or air flow. Either could produce the calm patch because a (relative) wind over the water of less than 23 cm/s cannot produce waves. Why is this?

A wave on the surface of water can be characterized by its wavelength and its speed. For the most familiar form of waves that buffet a boat or shore, gravity is the restoring force. For these waves, speed increases with increasing wavelength. Another (much shorter) form of waves are variously called ripples, capillary waves, or surface-tension waves. For these waves, speed decreases with increasing wavelength. The result is that there is a minimum speed, 23 cm/s, and a minimum wavelength, 1.7 cm, for waves travelling on water. An object travelling through the water, or a wind pushing on it that has a speed of less than 23 cm/s leaves no waves. This light breeze is a ghost — it travels over the water without disturbing it.

So, if the wind is < 23 cm/s, the water is smooth; if the wind is > 23 cm/s, the water is ruffled. But, how does the wind temporarily change from the higher speed to the lower one and then back again so as to produce a limited patch of calm water?

For this, we need to know something about the wind profile, the way the wind changes with height above the surface. A bit above the surface (in this case, maybe only 10 cm above) the wind is stronger. It is slowed at the surface by friction, but that slowing depends upon the roughness of the surface. A general rule is: the rougher the surface, the slower the surface wind; smoother the surface, the faster the surface wind.

The previous image is repeated and labeled. The arrow shows a gentle wind of somewhat more than 23 cm/s coming from the right. The water waves it produces roughen the surface and this slows the wind so that at A the speed has dropped below the wave-cutoff speed. However, that smoother surface allows the surface wind speed to increase so that at B waves are again produced.

What happened with that patch of smooth water can happen again and again to produce an oscillation between rough and smooth water. In the picture of ruffled water, below, there is a train of six smooth patches with a spacing of fifty to a hundred metres.

Many of the oscillatory forms seen on a lake have been given names. I have been unable to find a name for this pattern, and indeed do not even know if it has been described previously.

Mind you, it is understandable if no one has bothered with it. After all, the pattern is inconsequential for water management, hydroelectric production, fishing, boating, and ecology.

But, it is a delight.

I am not surprised that science is more concerned with utility insofar as it is funded by private interest. But this is potentially dangerous. Fortunately art is not bounded in this way. Analogously, art is often limited by taste and by what is true. Which makes art then poorer and can also make it dangerous.

Doug, both are driven by interest, but the source of that interest differs. Science is driven (at its best) by empirical data — what is demonstrably the case, whether it gives pleasing or not; art is driven by that which gives pleasure — itself a shifting sand.

A delight it truly is. Thanks for the ride, Alistair.

Just so you know, I’ve been printing out your posts on “ripples, gravity waves, wind-driven waves, wakes, beach cusps, convergence, divergence, long-shore drift, and patterns from rain,” and keep them in a little binder handy to the dining room, which looks out over Sky Pond.

This fall, I’ve greatly enjoyed rehearsing your various accounts of the beauty of physics, and look forward to doing so again come April, once the ice is off the water.